A nice story by Helena Hunt in Baylor’s Lariat.

Refuge in Waco: Syrian refugees look to find home at Baylor, MCC

By Helena Hunt, Staff Writer

Notes played on a piano stream out of an office in Roxy Grove. A piano pedagogy student bends over the black and white keys, playing what he came here to study, showing the work of years at Baylor.

The student is Damascus, Syria, junior Amjad Dabi. He has been studying the piano here since 2013. Dabi, like so many other students at Baylor, is also pre-med. After he graduates in 2017, he might continue to pursue music in graduate schools, or apply to medical programs. As any undergraduate, he is still deciding exactly what to do with the rest of his life.

But unlike most undergraduates at Baylor, Dabi is an immigrant from Syria. His home has been caught in civil war for about the last four years, since protests decrying the regime of President Assad began in March 2011. Dabi’s family still lives outside Damascus, which is largely controlled by Assad and pro-government forces but has also been caught in the throes of the conflict between rebel and government forces.

Dabi and his friend Andreh Maqdissi, who attends McLennan Community College, came to Waco in 2013. Dr. Bradley Bolen, who teaches piano at Baylor, was instrumental in bringing them here after meeting the two students at an American Voices workshop in Damascus in the summer of 2010. American Voices brings American music and instructors to young musicians in countries that have recently become independent, seeking to promote cross-cultural understanding and awareness.

As Bolen details on his blog, he first noticed Dabi’s and Maqdissi’s dedication and ambition during the workshops that summer. He kept in contact with them over the years and, as he noted the escalating conflict in Syria and the risks that both of them faced by remaining, he had the idea to bring them to the United States.

“The war was heating up, and these guys had done a great job of their educations and were actually close to finishing there. They decided, well, maybe they wanted to finish their educations and were trying to figure out how they could do it,” Bolen said. “In the process during that period I remember Andreh calling me having had a rocket grenade go across the front of his car, [which] blew up the building and the windows out of some of the cars around him.”

Although Maqdissi did not suffer any serious harm from the rocket grenade, Dabi suffered lacerations to his face after a car bomb detonated outside his home. Bolen calls these experiences a wake-up call for the students, who soon after left Syria for Thailand, where they stayed in an apartment owned by John Ferguson, the head of American Voices. Once in Thailand, they did not know whether they would be able to come to the United States or return home.

However, both Dabi and Maqdissi were accepted into their respective institutions with nearly full scholarships available. Seventh and James Baptist Church also gave them free housing once they arrived in Waco.

“Being at Baylor, I have met a lot of supportive people, starting with Dr. Bolen. The School of Music and the university have been extremely supportive of my education here and what I’m trying to do. I think it’s just been wonderful all along, in terms of having social, financial and educational support,” Dabi said.

Of course, Dabi’s mind is always with his family in Syria as well. Any phone call could contain news of a relative or friend’s injury or death.

“How many times do you expect to call someone in your family and the first thing they say to you is, ‘We’re all alive’?” Dabi said.

Dabi said that the obstacles to arriving in the U.S. were difficult for him and would be nearly insurmountable for his family. They are trying to bring his brother to the country, but financial and immigration difficulties remain a major impediment to his arrival.

The U.S. has so far accepted about 2,290 of the 4.2 million refugees who are fleeing the civil war in Syria. About 194 have come to Texas, which is one of the top six states for refugee resettlement. While President Obama pledged to accept 10,000 refugees in the coming year, the vetting and approval process can still take about two years.

That process may become even more demanding in the wake of the attacks in Paris. While no confirmed Syrian refugees were among the known attackers, the governors of 31 U.S. states, including Governor Abbott of Texas, oppose the entry of Syrian refugees. However, the authority to close state borders does not lie with these governors, but with the federal government. Several presidential candidates have also expressed opposition to immigration, or enhanced screening of potential refugees.

Dabi urges these lawmakers to consider the situation that these refugees are coming from.

“I would encourage people to actually look at the scale and the severity of this catastrophe, and for them to look up what the living conditions of these people that are living in refugee camps, or internally displaced in Syria, or even that are still living in Syria. Aside from the general war zone, there’s food shortages, there’s barely any electricity, nobody has any sort of fuel derivatives to warm themselves in the winter, and we’re coming on a very harsh winter. Just imagine living a day where you have no electricity, it is 20 degrees outside, and you have no means of warming yourself, and then imagine that happening every single day with no end in sight,” Dabi said. “I would also encourage people to look up whether such fears are actually rooted in truth.”

Bolen additionally urges politicians to look at the facts of the situation in Syria and the demographics of immigrants before closing our borders. He pointed to the thoroughness of the vetting process, saying that entry of refugees into the U.S. takes longer than for almost any other immigrant group due to the background checks that are in place.

Despite the difficulties he had in coming here, and the obstacles his family continues to face in Syria, Dabi is glad to have found another home in Waco.

“Being in a war zone sometimes it is hard not to lose faith in a lot of what humans can and want to do. But also, seeing the side of people who are willing to help, who are willing to take some time to [take] a great leap of faith in you, I think it’s the best cure for losing your faith in the world,” Dabi said.

Posted in Uncategorized | Tagged classical music, diplomacy, education, middle east, music, pianist, piano, Syria, Texas, Waco | Leave a Comment »

A nice story by AVERY LILL at KWBU. Audio available through link to story:

http://kwbu.org/post/syrian-refugees-look-resettle-texas-could-become-home

As Syrian Refugees Look to Resettle, Texas Could Become Home

In September, the United States announced it would aim to accept 10,000 Syrian refugees, as millions continue to flee the violence in their home country. , The resulting refugee crisis has raised many questions, like where can the displaced go. Is Waco a viable option? For KWBU Avery Lill reports

25-year-old Amjad Dabi describes what life in Syria was like before he came to Waco as a student in 2013:

“I mean, I remember, we’d be sitting down taking the exam, and would hear the shelling from near by and the, the walls and the windows would be vibrating,” Dabi said. “War sort of became, I don’t know, a daily part of life you don’t get used to it necessarily but you sort of acquire this ability to just go on and pretend that nothing bad is going to happen.”

Dabi and his friend Andreh Maqdissi met Baylor professor Bradley Bolen in 2010 through the non-profit organization, American Voices. Bolen kept in touch with the students via social media. But as life in Syria became increasingly dangerous, it became apparent that the two needed to leave their home country, so Bolen found a way.

“One of the local churches was very kind and offered them housing if they could make it,” Bolen said. “And we went through the audition and application process here at Baylor, and they were accepted. And one thing led to another and they ended up here and they’re thriving.”

But moving to Waco, also presented some challenges for Dabi. He says transportation was one of the biggest issues. In a city where waiting for the next bus to arrive can take up to an hour, it can be difficult to get around. But as Dabi notes, with optimism, the move to Waco was a good one. Bolen believes the city has all the benefits a refugee would need.

“Waco is a very loving place I think, in the sense that people look out for each other,” Bolen said. “Sort of got that small town atmosphere. So it may have made it actually a little easier in some ways to get help.

Getting that help, however, will be a long process for the thousands of Syrians who hope to come to the US as refugees. Before they can even apply for resettlement, they first must leave Syria and be granted refugee status in another country. In most cases, people who are allowed to come to the US as refugees already have family here. But, the US is more likely to consider admitting people who are in vulnerable situations – like the erupting violence in Syria – and who do not already have family ties. Regardless, the process can take a number of months depending on the situation. Aaron Rippenkroeger, CEO of the Refugee Services of Texas explains.

“The U.S. refugee program is not typically, it’s not designed for emergency, rapid fire action,” Rippenkroeger said. “It’s again those security checks are a very important part of that. And part of the slowness of it. And the thoroughness of it.”

Once approved for what is called a “third country resettlement,” refugees are referred to organizations like the Refugee Services of Texas. Of the 10,000 that the US has committed to welcoming in 2016, Rippenkroeger estimates that anywhere from 700 to a 1,000 Syrians will put down roots in Texas in the near future.

“I think we will see a slow, methodical increase of them in the next couple years. And I think we’ll start to see that uptake start to happen in early next calendar year,” Rippenkroeger said.

There are three main things that make a city a viable place for refugee resettlement: an open job market, available housing, and a reasonable cost of living. Rippenkroeger stresses that the benefits associated with resettlement are generally limited to six months, after which time he says refugees need to be self-sufficient. A city that supports refugee resettlement, receives aid – like School Impact Grants and health screening facilities – from state and federal governments to help develop its infrastructure. But while Waco is not currently a designated resettlement site, Rippenkroeger expressed optimism that it could be if the city expressed interest.

“Waco has all the indicators that would speak to a positive resettlement experience,” Rippenkroeger said. “But again if that were to happen it would happen very slowly, very gradually. Small numbers. You know, as community people and community partners become familiar with the program and how it works and the clients and the new community members that could be joining the community in that way.”

While it remains uncertain how many – if any – Syrians will relocate to Waco, there will be some relocating to surrounding cities, like Houston, which according to reports has an estimated refugee population of 70,000. But for Bolen – who helped Dabi and Maqdissi, resettle to Waco as students – whether it’s a big, metropolitan city or a small, rural town that receives the refugees, what matters is a welcoming community.

“I think it’s the Swedish chef on the Muppets that used to say peoples is peoples, right? I think that’s the moral of the story that people are people,” Bolen said. “We draw up boundaries but it’s not what’s important.”

Posted in Uncategorized | Tagged Baylor, classical music, diplomacy, education, middle east, music, pianist, piano, Syria, Texas, Waco | Leave a Comment »

[ WARNING: Some of the pictures below may be unpleasant to some. View with discretion]

When I crossed the border into Syria in the summer of 2010, I had absolutely no idea what to expect. Those that read my blog entry covering those colorful hours of travel may remember my apprehensiveness the evening that our American Voices faculty left Iraq and headed for Damascus.

.

This “shady” picture was taken at 3am in the morning, as we were negotiating under a highway bridge for “Syrian Taxis” to take us from Beirut to Damascus. Summer, 2010.

.

At our American Voices workshop at the Damascus Conservatory that summer, I was amazed at the plush facility (since bombed) and the many talented students I met there. Little did I know, but two of the students would leave a particular impression on me.

.

.

Damage to a Conservatory practice room, post bombing. The Conservatory is surrounded by parts of the Syrian military complex, thus making it vulnerable to collateral damage in any attack.

.

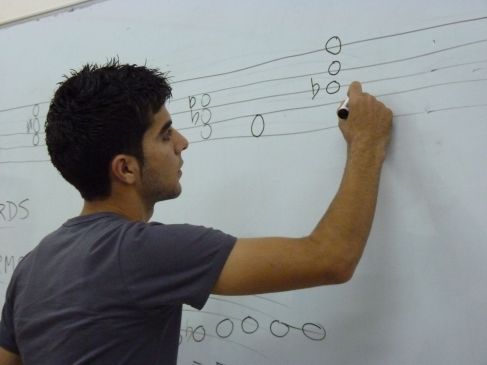

Amjad (piano) and Andreh (violin) were relatively quiet students in the early stages of the Damascus workshop. What I did notice was their particular love of their instruments, and the sensitive… philosophical…approach they took to their “trade.” In reality, it wasn’t really their trade yet, at least in terms of how most professional Western musicians might view things. But they had ambition. And as one can imagine from reading the news these days, it was not always under the best of circumstances that they pursued careers in music.

.

.

.

A year passed, and in 2011 I found myself in Jordan (Amman) doing a second summer tour with the YES Academy (Youth Excellence on Stage). Towards the end of that workshop, and to my astonishment, Andreh made a surprise appearance at a lunch at the Amman Conservatory cafeteria one afternoon. He had risked crossing the border of Syria by car in order to participate in the capstone workshop performances. Since the revolt in Syria had started (only months after I left in 2010), I was amazed that he had risked the odds to make the trip. At the time, the government controlled much of the country through which Andreh had to travel, so to Andreh it was a risk worth taking in order for him to be part of the final orchestral gala that ends each of the YES Academy workshops. Like the Syrian gala the summer before, the Jordanian gala had the advantage of being broadcast live throughout the country and much of the Middle East.

During our short visit, Andreh and I discussed the events in Syria and I caught up on news of Amjad (who was back in Syria attending school). After the well-attended gala performance, Andreh headed back to Syria, and I returned to Texas.

Thanks to email, Facebook, and other social media, it was easy for me to keep in touch from Texas. So as the summer of 2012 and my third tour with YES approached, I raised money to pay the tuition for Amjad to attend the YES Academy that was to be held in Beirut, Lebanon. Though it would only be a 3-hour drive through the mountains from Damascus to Beirut (and no sure thing the roads would be safe), I still had hopes that Amjad might be able to study piano with me again. At that time, I also had hopes that I would see Andreh and his violin again, as well.

But as the date of the 2012 Academy approached, the violence in Syria escalated.

Andreh, during a cleanup day at the Conservatory. A bomb blast nearby caused considerable damage to the buildings, and the instruments inside.

.

As things worsened in Syria, I chatted with both guys on facebook, and I began fostering the idea that they consider ways of leaving Syria altogether, suggesting that it might be prudent for them (and the future of their families) for each of them to search out their musical aspirations outside of that country. John Ferguson (founder and CEO of American Voices) owns some apartments in Bangkok, Thailand, and generously offered them refuge should they choose to leave. For each of the guys, such a major decision would carry with it different, but equally weighty, considerations. In my view, both young men were of “fighting age,” and to be caught on the streets by the wrong parties would likely be fatal. I couldn’t have been more adamant that they should leave, even though I worried that I might be making a mistake should they leave and circumstances keep them from returning home someday.

It was only the second day of our 2012 Beirut workshop, and any realistic hope that the guys would be able to attend had vanished. By then, the conditions of the war had deteriorated enough that it stopped any but the bravest or desperate of Syrians from making crossing into Lebanon. But on that day, I was in a car headed to the University to teach and who should jump in for a ride…but Andreh, together with his trusty violin!

When I asked what he was doing there, and asked where Amjad was, he said that Amjad had been forced to stay in Damascus to take exams. (Due to the war, the conservatory had to delay its finals. They were now scheduled during the date of our YES Academy and, as a result, Amjad had little choice but to stay in Damascus to take them. Amjad was also studying engineering at the University….so exams there may have also been a consideration). Andreh also explained that, due to fighting that had broken out near the Syrian/Lebanese border, the border closed behind him only moments after he had successfully crossed, thus leaving him unsure whether or not he would even be able to return to back to his home in Damascus when YES was over. But as in Jordan, the YES workshop was Andreh’s motivation and nothing was going to stop him.

The night before I left Beirut at the end of the two weeks of classes, Andreh was still unsure of his future. He had only brought a couple of hundred US dollars with him to Beirut, and that was running low. And with the border closed, we were unsure of how he would hold out in Beirut. So, I forwarded him a couple of hundred dollars and wished him the best, even if the best was to secure a job in Lebanon in order to sustain himself. To my surprise, a couple of days after my return to Texas, I received an email explaining that he had used the money to hire a “taxi” to risk the return to his family in Damascus. Thankfully, that trip was successful and the travel uneventful.

The same couldn’t be said of the months that would follow.

Both Amjad and Andreh are from a suburb of Damascus. President Assad and his government forces have largely controlled that area of the country. However, by fall of 2012, rebel forces had made such inroads that safety in the streets of Damascus was anything but assured.

The trouble hit home for Andreh one afternoon as he was out trying to sell his laptop computer. On the way home, he made a “wrong turn” and found himself in the middle of a firefight between Syrian rebels and forces loyal to the government. “I didn’t think I would make it out alive,” Andreh texted me, clearly shaken. “I thought that was it, and I was going to die.”

After getting approval and support from his family, the decision to leave Syria was made. After consulting with John in Thailand, American Voices paid for the air ticket, and Andreh left Syria, not knowing if he would ever see his family again.

For Amjad, who was still in school in Damascus, the decision to leave rested not only on his reluctance to leave his family, but also in a balancing act between predicting whether or not the regime would survive, or whether the rebels would win. One miscalculation could effectively end his education. In Syria, if a young man has a brother, he can be drafted into military service…unless he is enrolled in school. Andreh is an only son, and didn’t have the draft consideration. But Amjad has a brother, so for him to leave the country would have meant that he might not be able to return should the war result in a rebel victory. Should the government win, his return might be possible, provided he follow papers through a Syrian consulate which would allow him to postpone the draft every year and return to Syria without facing arrest. Of course, it was the “postpone” caveat that caused us the angst in this scenario. For Amjad to postpone his conscription into military service, it would require him to be in school. In other words, it depended on his ability to score high enough on the aptitude tests and play a strong piano audition, not to mention raising the funding to attend a university. Anything less would result in the cessation of his musical aspirations, as well as leave him stranded from Syria and his family.

For several weeks…or was it months…I begged Amjad to leave. Then, on one fateful day, a car bomb exploded outside of his house, lacerating his face. Indeed, Amjad was lucky. What was meant to be two car bombs resulted in only one explosion. The first was meant to attract help into the street, only to have the second do the “real” damage. Lucky for Amjad, the first didn’t detonate. For Amjad, the decision to leave was made. In order to have the best chance to forward his education, and perhaps to even survive, he would have to leave Syria. Again, John came through with housing in Bankok, and again American Voices paid airfare for the trip, and both of the guys came to share an apartment there as they sorted out what to do next.

.

.

.

It was fall of 2012, a time in which many American seniors typically take their SAT’s and apply to schools throughout the country. For Andreh and Amjad, they would have to prepare not only to take their aptitude tests, but they would also need to prepare musical auditions, as well. With an emotional focus on the well being of their families back in Syria, and with every reason to feel detached and distracted from their new surroundings in Thailand, both studied and practiced, and managed to find a small studio in Bangkok at which to record and re-record their musical audition tapes. John, also a pianist, worked with Amjad, though John was often out of the country paving the way for the next YES Academy workshops. I supplemented with a couple of piano lessons via Skype. Andreh found a teacher in a local orchestra to offer him occasional guidance on the violin. Frequently, I would receive an email attachment of part of their potential audition material, accompanied with the question, “Dr. Bolen, is this good enough?”

As long as the odds could have been, I am happy to report that both men scored not only well enough to gain acceptance into their respective colleges (Baylor University and McClennan County College ), but both performed well enough to receive the largest scholarships either institution offers. Needless to say, this was thrilling enough for all of us. But, just as the way seemed paved for them to come to America for study, there would be visa issues, housing issues, and issues of “petty” finance that all students know too well.

For much of the year, I felt as much like an immigration lawyer as I did a pianist. One of the biggest decisions was whether or not to have Andreh apply for his visa with his Syrian passport (as his father is Syrian) or his Russian passport (his mother is Russian). After some deliberation, it was decided that the Russian passport would be the safer route, as the connotations that can sometimes go along with being from the Middle East, let alone a war torn country, could ultimately make things more difficult. Only a month passed after his application, that the Boston Marathon bombings happened…as the result of Russian born extremists. My contacts with congressmen and senators made it clear we might have problems.

But, little by little, things began looking up. The biggest news came when an application I put in at the local Seventh and James Baptist Church for housing was approved. The church has a long-standing tradition of helping international students in need. Each year, such students occupy one of 5 apartment units the church owns under their “Dunn House” program, and the church pays their rent and utilities for their duration of study. We also managed to get financial documents from various sources – myself, the church, the schools — indicating the guys had at least some support. The result was that both guys received their visas the day of their interviews in Thailand, a better than expected outcome.

Even still, neither Amjad nor Andreh have families with the resources of the typical American college kids. And in the last few months, the crash of the Syrian currency, along with a 92 percent per month inflation rate there, destroyed any hope for additional help from their families for day-to-day finances. The total destruction of Andreh’s father’s factory didn’t help matters, either. During the last year, both men lost friends and loved ones to violence, Andreh even having his cousin beheaded at a roadside checkpoint.

Both Andreh and Amjad will arrive in Dallas on August 1st. I will be picking them up from the DFW airport. On that day, they will arrive with little more than they can fit in their pockets, or that their scholarships will ultimately provide.

And on that day, both will be two of the happiest people on the planet Earth.

Posted in Uncategorized | Tagged Amman, classical music, diplomacy, education, Jordan, Lebanon, middle east, pianist, piano, Syria, violin | 1 Comment »

.

THANK YOU!

.

It was gratifying to get a little press over the last month on behalf American Voices and the “kiddos.” Below, I have pasted a few links from some of the news outlets that have covered us.

If you have enjoyed hearing about our work, (or if you are hearing about us for the first time), please consider a small donation to either American Voices, or the newly created Baylor School of Music American Voices Scholarship Fund, and help us make a difference. Help us help these young talents in a part of the world that might not easily find such opportunities elsewhere.

Thanks to all for their support!

NATIONAL PUBIC RADIO:

http://edge.baylor.edu/media/183996/183996-audio.mp3

WACO TRIBUNE

KXTX TV

http://www.kwtx.com/video?autoStart=true&topVideoCatNo=default&clipId=7618958#.UCyEQ9jPgzg.facebook

KXTX WEB

http://www.kwtx.com/ourtown/home/headlines/Waco–BU-Professor-Teaches-Music-In-Iraq-166961596.html

DONATIONS

.

American Voices:

http://www.americanvoices.org/support/

The Baylor School of Music Scholarship Fund (type name of this fund in the box at the bottom of the page):

Posted in Uncategorized | 1 Comment »

Back home in Texas. Throw me a kitty, it is time for a nap.

The gala concert in Lebanon was a success. The fact that it took place at all wasn’t taken for granted.

In the preceding months, we had originally planned on a full workshop on the University of Notre Dame campus in Lebanon (our program in 2010 was on the American University campus). The plan was to include around 10 YES Academy faculty. But due to the unrest in the area (specifically in Tripoli, a few clicks north of Beirut) we decided to cancel the program just prior to our departure for Iraq at the beginning of July. The Lebanon program was on and off again twice, and in the end, and after some serious discussion, John, Marc, and I decided to do a limited program there with just the 3 of us. There were quite a number of pianists registered (enough that it would take both John and I to handle the 40-student load), and there were enough string players that Marc would have his hands full leading them. My decision to go was also a tough one because my wife (Lynne) would be departing for a four month gig in Africa only a week after my return from Lebanon. In the end, we decided that my participation would be a net positive.

Thankfully, all of the YES programs went off beautifully, including the questionable decision to do a 4-day mini workshop south of the river in Kirkuk, Iraq.

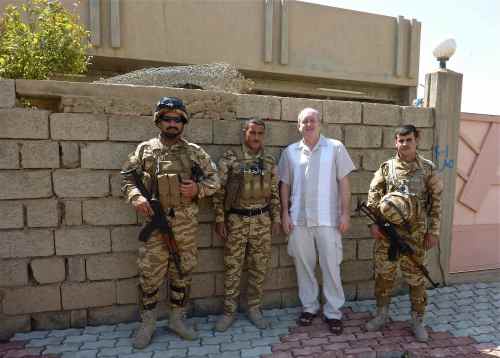

At the request of the US Embassy, 6 of us were asked take part in the Kirkuk mission, while Marc, John, Bruce, and Michael headed to Baghdad for concerts there and in Basra. In theory, their trip would be the “dangerous” one, and they would have to travel by armored vehicles while wearing full body armor (the picture of Bruce in a helmet and flak jacket while carrying his cello made for a humorous juxtaposition).

We were told that we would be staying north of the river in Kirkuk, where Kurds make up the majority, and where violence has been at a minimum. We were to arrive at a house equipped with four small rooms in which to do our teaching, and be in and out within 3 hours on each of the 4 days we were scheduled to teach. But on our first trip on day one, we unexpectedly found ourselves being shuttled over the river, and a couple of miles into questionable territory. Security was tight, and we now know why.

Only a few days after our departure, coordinated attacks throughout Iraq killed over 100 people, many of them in Kirkuk. One of the 8 reported bombs in Kirkuk hit the police station next to the Children’s Center where we worked, and blew the windows out of our building. As of yet, I have not heard directly from any of the students there as to their safety after the attack, but word is that everyone is ok. Needless to say, John was less than happy after returning from Baghdad to find out our venue had moved without warning. But in retrospect, the faces of the children after our capstone mini-concert at the Center made the risk worth it.

Below are a few pictures and videos of my experiences this summer.

A special thanks to all who made donations to make our programs possible.

Enjoy!

.

.

.

.

.

.

A single American girl in Iraq? You bet! And the Iraqi guys wasted no time in serenading Bethany (YES Academy Children’s Theater faculty) with a folk song during lunch on the first day of classes.

.

.

YES Academy founder, John Ferguson, visits composer Patrick Clark’s composition class to give a lecture on Frederic Rzewski’s “Winnsboro Cottonmill Blues.”

.

.

With only one day to adjust, the first day of teaching can be a weary experience. But, I give it my all during pedagogy class.

.

.

One of Patrick’s composition students gets his composition for santur and orchestra read. This Persian instrument is related to the Dulcimer.

.

.

We managed to get out to the bazaar a couple of times for some evening shopping and people watching. Making new friends was easy in Erbil, Iraq.

.

.

Located in Erbil’s old souk, this may be the most famous Tea Room in all of Iraq. The walls are covered with pictures of the famous people who have visited over the years. The owner was quick to point out that Joe Biden had recently visitied.

.

.

It was common for us to be invited to the homes of our students for lunches or dinners. The food was incredible, and the traditional Kurdish dress of some locals was a treat, as well.

.

.

One of my favorite experiences was getting to hear locals play their traditional folk instruments. This turkish instrument is not unlike the Banjo.

.

.

.

.

We crossed this bridge when we got to it. We weren’t supposed to. In Kirkuk, south of this point means more risk.

.

.

.

.

The road in Kirkuk was rough, so holding the camera still wasn’t easy. But, perhaps this gives one some idea of the look of the city.

.

.

Simple logistical problems can ruin an otherwise good day of teaching. While driving through Kirkuk, Mariano (jazz faculty) lightens the mood by venting about a student volunteer who went MIA when he needed him for the use of a printer.

.

.

When a tanker crashed on our trip out of Kirkuk on the third day of our mini workshop there, our security team got us out of harm’s way. We weren’t sure what was going on, and it made for an interesting ride. I took this video during the event.

.

.

The reason we went to Kirkuk. This little one played a chicken in the children’s theater production on our last day.

.

.

Our Lebanon apartment. Our third floor balcony overlooked downtown Beirut and the sea on one side, and the mountains on the other. Ahhh….

.

.

.

.

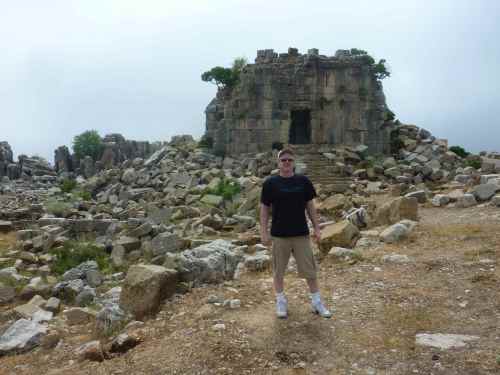

A trip into the mountains during our one day off in Lebanon unexpectedly landed us at the Roman ruins of Faqra. Yes…that’s me and my nerdy white socks.

.

.

Another view of the Faqra ruins. Fog added to the mood of the place.

.

.

This natural bridge is near the Faqra ruins. Look closely and you can see two people walking above it, giving some perspective as to its size.

.

.

It is Gala Concert time in Lebanon. The concert hall rests on the Notre Dame campus, just above the sea.

.

.

.

.

Mario learned this Morton Gould Boogie Woogie Etude in 3 days, and performed it for MTV and the Gala. Nice work, Mario.

.

.

.

.

Until next year’s fireworks…that’s a wrap!

It’s a Lebanese festival!!!

Posted in Uncategorized | Tagged classical music, diplomacy, education, Iraq, Kirkuk, Lebanon, middle east, music, pianist, piano | Leave a Comment »

There is more than one way to fight, or so they say.

We at American Voices do not charge ourselves with teaching beginners. Instead, we fight to help those that already have some training to move forward with their musical aspirations, and to provide some thread of continuity to their broken educations. Of course, in reality there are those that, for all practical purposes, are essentially beginners (we sometimes even add a beginner class if the need arises). This results in an additional amount of classroom diversity that presents its own set of challenges.

It has been difficult to blog since work has been so exhausting and, since this is my second trip to Kurdistan, because I now know people here who are anxious to take me out for dinner or the markets once work is finished. Or, as Grandmother used to say, “Just so you know, it is hell to be popular.” It is hard to describe how one can feel so fatigued and still have so much fun. It is a daily ritual.

This year, the YES Academy was plagued with a plethora of logistical challenges. But the final Gala in Duhok went off as planned, which is a good thing since the new conference center at The University of Duhok is state of the art, and only months old. A beautiful venue.

The foyer of the University of Duhok conference center. The front steps open up to a view of the entire city.

.

.

.

.

Two of my special students, Mohammed Akmed (Baghdad) and Hersh Akram (Erbil). I worked with both of these talented buys in Erbil in 2010. Hersh will be attending East Carolina’s ESL program this fall, where he will also study piano. Unfortunately, my city currently has no ESL program available. Our loss.

.

Once the gala was over in Duhok, we were back to Erbil. We were asked by the US Embassy to do a 4 day mini-workshop in Kirkuk. To do this, we would have to take special security measures. While Kirkuk is much better than it was even a couple of years ago, it is still a city in conflict. Though there is plenty of oil in the Kurdistan region of Iraq, Saddam had not allowed the Kurds to drill for it (which is now beginning to change). Since Kirkuk is on the southern border of Kurdistan, and is so rich in oil, Saddam began moving Arabs into the area during his reign over Iraq, and exploiting the resources of the area, thus creating a dispute as to whom Kirkuk actually belongs. At this time, it is technically part of Iraq, and not a part of Kurdistan, though the northern side of the river (the side we would be visiting) is made up mostly of Kurds who will be quick to point out that the city is theirs.

Our security team consisted of 11 Kurdish Peshmerga soldiers, and would be supplemented by extra police during our mini concert that would cap our 4 days there (I was on the local news in Kirkuk the night before the concert, so any “baddies” that wanted to cause trouble would have known to whom and where to go to make it so. It might be noted that I asked the media folks not to broadcast the story until the night we would leave. Their response was an unconvincing, “we will try.” I guess some things are the same no matter where you are).

In reaching our destination, one of the “Kurdistan Save the Children” centers, we were not be able to take the same route each day, nor would were we allowed to stay the night in Kirkuk. We had to change cars on the outskirts of town each day so nobody would be able to recognize our cars when we entered the city.

To be honest, I wasn’t so much worried about our security in terms of terrorism as much as I was worried about the driving we were subjected to…100 mph, with no seatbelts, and a driving style that would get anyone attempting it in the States arrested. The highway is crowded with tanker trucks carrying petrol, and in 4 days I saw 3 crashes on the short 50 mile stretch we would travel. When I scolded the commanding officer on the second day for deliberately trying to get as close as possible to the cars as he passed them (it wasn’t necessary to get so close since we had two lanes, and I saw several cars run off the road by our vehicles), his response (via a translator) was that we had to drive that fast for security. I retorted that I didn’t give a damn how fast he drives, but that he didn’t need to cut tankers off by a coat of paint, and I asked him what good it does us for him to protect us with guns if we would end up dead in a ball of flames. Moments after this conversation, we came upon another tanker on fire on the highway. Our caravan didn’t waste any time getting off road and out of harms way. After a 5 minute improvised (and very bumpy) route through what looked like a industrial park yard, we were back on our way. Somehow, the ride afterwards seemed more reasonable. While Paul was more concerned about the driving in town (we hit two cars in 4 days in my car), i was more worried about the highway. Regardless, the whole experience would be quite an adrenaline rush by any standard.

.

.

One of three semi trucks we would see crashed on the short 50 mile strip of highway to Kirkuk. Drivers here are quite simply insane.

.

.

This is the main checkpoint out of Kurdistan and into Iraq. Of course, technically speaking, Kurdistan is part of Iraq, which goes to show one that things here aren’t quite as simple as they may seem.

.

.

We changed cars each day at the commanding officer’s house on the outskirts of Kirkuk. We did so to avoid being identified by the cars we drove everyday. The soldiers gave us water, and some lively conversation.

.

On the last day, at our car change point, we gave the soldiers some sweets to thank them for their work.

.

.

.

These “cooling stations” are located along the highway between Kirkuk and Erbil. You just pull up and a hose cools the radiator. In the 115 degree heat, the cars need all the help they can get. You can usually buy drinking water here, as well.

.

.

Racing through town. The military guys insisted that speed was important in order to keep us out of harms way.

.

This is where one buys gas for their cars. A fixed station offers too easy of a target for destruction. These mobile sites litter the sides of the road in the city.

.

.

.

About 10 minutes after I barked at the commanding officer for reckless driving. To get us out of potential harm’s way, they took it off road, and fast.

.

.

.

Paul finally got his wish, and on the last trip back to Erbil the soldiers let him ride in back with them. Though he had a blast, he quickly learned that a 100 mph blasting 115 degree wind isn’t for the faint of heart (or those without the proper clothing). He spent the last half of the trip back in the cab.

.

Our final visit at the car change location. On the way back, the soldiers with Paul were singing Kurdish folk songs and singing wishes that these time should never end.

.

The nice thing about the Kirkuk run was that we were back at our hotel in Erbil by 3pm each day. Since we have been staying near the city center, there has been plenty to see after working hours.

.

Walking to the Citadel in the middle of the city. Believe it or not, the wiring gets LOTS worse than this in Kurdistan.

.

.

The shop owner in the bazaar screamed at me for taking a picture of his vegetables. I guess that they weren’t properly dressed.

.

We met somebody new on just about every trip we made outside of work. These guys were hanging out in the plaza. Paul speaks pretty good Arabic, and often made friends easily.

.

We had a nice chat from this couple from Mosul. They have been married 46 years and the man was in Erbil for medical attention on his knees.

.

.

One afternoon, my students, Hoshyar and Hersh, took me into a back alley neighborhood near the town’s bazaar. It was the Jewish quarter up until the 1970’s. Saddam ran the Jews off, however they officially still own the homes in the area. Hoshyar and Hersh both wish for the day they will return. The government is currently moving out the people in these homes in an attempt to accomplish just that. My guess is that they will never return. Most of the homes are in ruins and the political climate doesn’t favor the immigration of non-Kurds or Arabs.

While walking the narrow streets, my original idea was to be on the lookout for my usual cat photo ops. I noticed that the streets weren’t filled with cats, but filled with children, their parents mostly indoors preparing dinner. So, I put away my camera and took out my iphone in an attempt to stealthily (but mostly not so stealthily) use the phone’s camera to take pictures of the children in an attempt to capture a glimpse of their lives in this part of town. Since I took these photos “on the fly,” the focus is not always the best. Still, if you look closely, you can see clues as to the nature of their meager existence here in Erbil.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

Though I am very tired, I am confident that we accomplished some things here. The final look on the faces of our students told us we “done good” in Kurdistan. I am off to Lebanon tomorrow, where a record number of pianists await.

.

Posted in Uncategorized | Tagged classical music, diplomacy, education, Kirkuk, Lebanon, middle east, music, pianist, piano | 4 Comments »

They are called Aggies. And to a Baylor Bear, they are like gremlins. Lynne (my wife, who joined me her for the first week of my adventure) and I counted no less than 10 of them on our flight into Erbil, as they were arriving to act as consultants on agricultural issues in the Kurdish region of Iraq. I braced myself for mechanical mischief on the plane. Nope…looking out the window, I didn’t see any of them pulling panels off the wings. We would land safely after a long and very uncomfortable flight. There have been a few other times to be suspicious that they were at work around here, however.

Take, for example, the bathroom stalls in the Humanities building here at the University here in Duhok. They seem normal enough, overlooking the bank-like security locks on the front that require a key, with a heavy metal door and only a small opening along the top for air. The toilets themselves are the “old style” that travelers may be familiar with. Porcelain holes in the ground with nothing to sit on. (The logistics of using one of these still escape me.)

When one of our faculty members, Patch…one of our children’s theater profs…went to school in the morning to get work done on Thursday, she found herself locked in the second floor stall with no way out. By the time we heard her screaming, she had been there for 10 or 15 minutes. In her words, it was as terrifying as it was pathetically hilarious. Nobody had a key, and she thought she might just be able to jimmy it open if only she had a simple screwdriver. We looked around in vain, as her panic was evident. Finally, when Paul “The Rocket” Rockower (our excellent new communications director) realized he had a swiss army knife with a built in screwdriver, he was instructed to toss it over the opening to Patch.

Nothing but net.

The knife didn’t even touch the sides of the 3 inch hole it disappeared into. Patch was trapped for some time before she was freed. Others have apparently suffered the same fate as Patch. Paul has become quite adept at kicking in locked stall doors. As he puts it…”I am greeted as Liberator.”

And speaking of toilets, there is the one that lives in my room. The shower has no hot water (most of the time), but the toilet does! Hot water somehow makes it way into the bowl on its way past the shower. It is an interesting, steamy, sensation (which I think has marketing potential in the frozen north of the US). And every few hours “Old Faithful” nearly blows the top off her porcelain lid as she spews water over the bathroom floor (Video at 11, if I ever catch the event in time).

The design just has that “Aggie feel” to it.

Even as I am on the lookout for other potential traps, the truth is that Duhok is a wonderful city, cradled in the mountains, and filled with some of the greatest hospitality imaginable. The drive in from Erbil was easy, and it is hard to believe that this is the same city I witnessed in the youtube/journeyman video “The Fall of Duhok”. I am told that only three years ago that the highway from Erbil, now modernized, was barely navigable. Most every car on the road (and there are too many) are 2010 or later models (This is mandated by the government, and after asking a half dozen Kurds I still don’t have a consistent answer as to why). New construction is of a magnitude that defies logic. This is a boomtown in a region that, in reality, is a net exporter of nothing.

.

Besides a nasty fall down the stairs of the hotel this morning (resulting in a bruised hand and cut toe) everything has gone smoothly, particularly with my students; an attentive class of 15, complete with three translators, one for Sorani Kurdish, one for Badini Kurdish, and one for Arabic. Waiting for translations slows things down a bit, but also gives the students a kind of defacto discussion period for each new idea that I throw at them. Class meets from 10 to 1pm, and again from 3pm to 5pm. We cover sight reading skills, piano literature, pedagogy, technique, and prep for the final performance gala, which will be held on the 12th of this month. Evenings are free for dinner, or a quick trip to the market.

.

.

At the orientation meeting, a Children’s Theater student is excited to begin documenting her experience with the YES Academy.

.

.

Lynne took these photos of Michael Parks giving the dancers a workout. They put in long hours and the routine is physical. Emotions from these guys often run high.

.

Michael congratulates on of the dancers for getting it right. Or, maybe he is ripping his head off. It is never for certain during rehearsals.

.

.

.

Though one can easily move about freely in Kurdistan, Lynne was sequestered in the hotel for several days until we got our footing. But on Thursday one of my translators took her on a day trip to site see and to visit the top of a nearby mountain. Friday is holy day, and we seized the day off and headed for the ancient site of Amadyia.

.

.

Lynne photographed one of Saddam’s homes overlooking Duhok, complete with helo pad, on her day trip on Thursday. The home has been looted, and many of the stones of the facade are missing.

.

.

Lynne at the top of the mountain on her day trip. It is hard to describe how vast the landscapes are here, and pictures do no justice to the views.

.

.

Lynne left for Texas yesterday, and we finish up in Duhok on Thursday. It is off to Erbil on Friday. Word is that Lebanon is on, and I am eagar to see old friends there.

Stay tuned.

Posted in Uncategorized | Tagged classical music, diplomacy, education, Iraq, Lebanon, middle east, music, pianist, piano | 1 Comment »

As I cross the big water to Kurdistan, I leave an America assessing the ramifications of the Universal Healthcare ruling passed yesterday. If the markets are any indication, the money is betting on optimism. I am optimistic, as well, but under no illusion that a day means anything. Only time will tell.

When I arrive in Erbil, I will be greeted by, among others, my driver to Duhok, as well my friend Dr. Omar (who I blogged about during my 2010 visit). Besides being happy to see him, I will be pleased to deliver his new Kindle. Since Iraq has no banking system, and thus no credit card options, it is impossible to order even the simplest of items via the internet. The problem becomes even more complicated by the lack of a reliable postal system (I am told a fair number of items are mistakenly delivered to neighboring Iran. As long as I am not delivered there, I am cool…but Omar offers only laughing assurances on that matter).

Omar was up until recently unsure of his ability to meet me at the airport, as his job at the hospital has been exceptionally demanding of late, since most of the doctors in Erbil have been on strike. Omar chose to stay on the job, however. He works in the infant critical are unit, and as he explained, “if I don’t show up, the little ones will die.” The situation has me wondering how many other folks are suffering without doctors there, and trying to imagine how much worse things might have to be before others in his profession follow Omar’s lead. He isn’t working from a government mandate, but rather from a conscience. For some reason, his dedication reminds me of something my father said to me on more than one occasion, and something he communicated to his friends via a lifetime of actions: “Leave each place better off than you found it” (and those few that may have read my Facebook quotes may recall seeing that little gem). In reality, Grandfather emphasized the ideal to my father (I even recall “Popo” attempting to instill it into me directly, though I think in a vain attempt to get me to clean my room).

And speaking of Facebook…mine changed this year.

I am not talking about the switch to “The Timeline,” which I am still convinced Facebook deceptively trapped me into (I was under the impression that I could switch back if I clicked on the “try it” button. TRY IT, they said). No…I am talking about my “newsfeed.”

Yours may look something like this:

Wedding pics

Picnic photos

Zippy quotation

Farmville request

Sunset photo

…etc.

Mine looks like:

Wedding pics

Picnic photos

Pile of bloody dead bodies

Zippy quotation

Farmville request

Sunset photo

Video of child sitting on a table with his jaw blown off.

Of course, most of the unpleasantness (of this scale, anyway) comes from Syria. They want me to see. They want US to see. And the video of the child — probably 12 or so years old, sitting up on a table with everything from below his nose to his adam’s apple removed by an artillery blast in Homs — brought it home to me (I was told he lived two whole days with the condition).

I can tell you that watching something like that makes a difficult transition in turning away from the computer to teach a piano lesson. He could have been one of my students.

Amjad Dabi is one of my students, and this year I raised the tuition money for him to leave Syria to come study with me in Lebanon during our planned summer YES academy (Thank You, Susan). But with the spill over of unrest from Syria into Lebanon, American Voices finally had to cancel the program there (at least as it stands at the moment). A week ago, a live chat with Amjad on Facebook revealed his disappointment, even as two large explosions near his home in Damascus interrupted our conversation.

But during this year, there was one constant during my correspondence with Amjad and my other Syrian friends… my students in Iraq, Lebanon, and even Jordan…and regardless of their circumstances:

Music.

So, for the third year in a row I am heading back to a region that is divided and unstable (Though Kurdistan itself is quite stable at the moment). I have been asked a thousand times why I am going, and I am not always sure I can give a concise answer. Is it simply to put something interesting on a resume, or an attempt to bolster my visibility at my University? Is it to engage the most eager body of students I have ever met, or to try recruit top talent to Baylor (One of my fine Lebanese students pieced together a full scholarship for next year, but his circumstances will now forbid him from using it). Or, can I just claim “the greater good?” My guess is that all of these things come into play to some degree, and then some. Ultimately, what I would like to believe is that it is an attempt to follow my father’s mandate, the way some view the mandate passed this week in America, and the mandate Omar has chosen for himself.

“Leave each place better off than you found it.”

Posted in Uncategorized | 1 Comment »